A rule tweak at the end of 2017 allowing one-on-one steals to be executed in multi-tackler tackles provided only one defender was involved at the time of the strip saw the tactic proliferate last season.

As we head into the third season of the new rule interpretation, NRL.com Stats has taken a look at how the practice has evolved, how it may evolve further and what implications that may hold.

What happened in 2019?

After little change in 2018, the first year of the new interpretation, one-on-one strips proliferated in 2019.

The Raiders in particular and also the Storm got better at surprising teams by using secret code-words to co-ordinate for extra tacklers to drop off, leaving one man to effect a steal before the ball-carrier realised he was in danger of losing possession.

There were 120 successful steals through the 201 NRL matches in 2019. That is up from 68 in 2018 when the rule was first changed (the Raiders again were top with 11), and 44 in 2017 under the old rule.

One-on-one strips focus

The Raiders (28), Storm (19) and Warriors (11) were the only clubs to hit double digits in 2019. Josh Hodgson (14) individually effected more than 14 other clubs.

Teams were generally good at ensuring they didn't infringe once they decided to attempt a steal – there were 25 penalties for stealing the ball where it was deemed there was more than one in the tackle.

There were a further 232 penalties for a stripping action however these are the ones where the ball pops free in a tackle and it is deemed a defender hit or raked at the ball so there is no deliberate stealing action.

The ref's job got harder; coaches were critical

For the most part the officials did a remarkably good job of deducing in a split second at what point the extra tacklers dropped off and at what point the ball came free.

With the practice likely to increase further in 2020 as teams aim to emulate the Raiders' success, things won't get easier for the officials.

The officials have to make the calls in real time (unless there is a rare instance of the steal directly leading to a try) so they do not have the benefit of video replays.

They didn't always get it right; for example frustrated Warriors coach Stephen Kearney lashed out after a couple of tight calls incorrectly went against his side in a 24-22 loss to the Eels in round 19. "If they can't get it right … just piss it off," Kearney fired.

Roosters coach Trent Robinson and, perhaps surprisingly, Raider coach Ricky Stuart have publicly criticised the rule.

Robinson believes it is not in the spirit of the game and says his team will not be coached to do it (the Roosters registered just three steals in 2019) while Stuart suggested referees were being forced to guess when the extra tacklers drop off.

Fans liked it

The reception has been largely positive from fans on both social media and in official fan surveys.

For the most part fans appreciated the unpredictability and the chance for momentum swings in a game where possession is at a premium and can be hard to claw back once the tide turns against a team.

The NRL's head of football elite competitions Graham Annesley touched on issues around the rule during his weekly briefings several times and, while admitting it placed extra pressure on referees, broadly supported the positive reception around the increase in unpredictability and renewed contest for possession.

It got scrappy at times

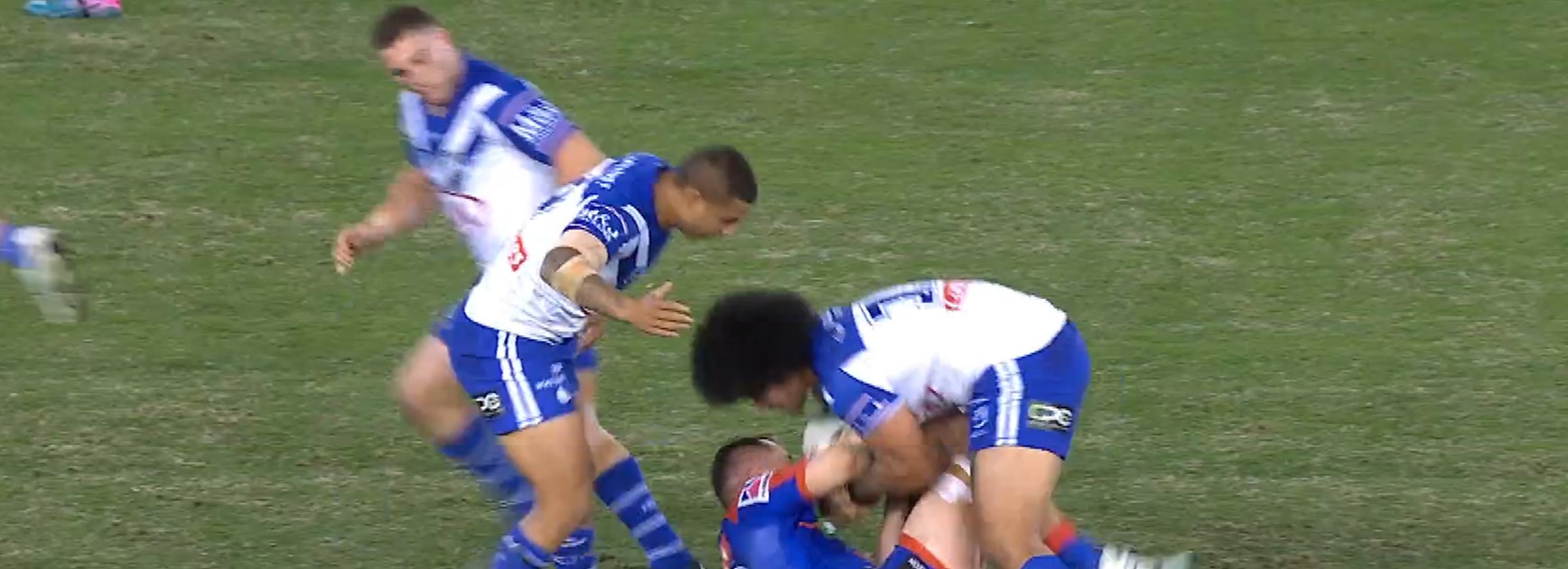

One of the looming issues for the rule in 2020 is what actually constitutes "one-on-one". NRL.com Stats has isolated a number of incidents from 2019 where a ball-carrier was effectively gang-tackled, with defenders wrapping up his legs and non-ball-carrying arm while another defender started prising the ball out.

The extra defenders drop off with the steal largely effected already.

So while defenders of the new rule say "if you hang onto the ball you won't have a problem" that doesn't always hold true, as the attached examples highlight.

Some have expressed concern coaches may become so worried about having the ball ripped away, players would be instructed to wrap it up tightly in carries and put the offloads away. There has been no evidence of this yet but 2020 could be the acid test if more clubs work on the strategy.

So is there a problem?

NRL.com Stats has collated some examples that most clearly highlight the issue in the above video and still shots. Each was deemed a legal strip at the time, and resulted in the team executing the strip gaining possession.

These selected examples are at the more extreme end of a ball carrier being wrestled by one or more defenders while also being stripped by another. However, they do not represent the majority of instances of one-on-one strips.

In all, there were 120 steals in 2019, from 201 total games, at a rate of slightly over one steal for every two games.

Of those 120, some would have been legal one-on-one steals even under the old interpretation and in many more the stripping action largely occurs in a one-on-one scenario despite earlier involvement from an extra tackler or tacklers.

Less than a quarter – which would equate to roughly one instance per round of eight games – bears similarity to the attached examples.

So, at this stage, there is no epidemic of messy gang-tackle steals. However as we have seen with countless previous rules and interpretations, coaches are smart. Their concern is winning games. If they sense a chance to earn an advantage, they will explore it.

Will we see more cases like these examples in 2020? If so that would test the interpretation. If the above examples become more common that could have a detrimental effect on the game as a spectacle and raise questions about fairness.

How the Perth NRL Nines will work

Captain's challenge could put a microscope on stripping rule

The details are still being worked out but a challenge system will be in play in 2020.

A by-product of this is for the potential for steals to be adjudicated on by the Bunker with slow-motion replays rather than by on-ground officials on the fly.

If a captain believes his player has been unfairly stripped but play has been allowed to continue, he will be able to send that play to the Bunker.

This in turn could force some clarity around what happens in situations like those outlined above.

What is the rule, and will it change?

The reworded rule concerning stealing the ball is as follows:

a. The ball can be stolen from the player in possession at any stage prior to a tackle being complete when there is only one defender effecting the tackle;

b. If there are two or more defender[s] effecting the tackle and the ball is stolen a penalty should be awarded, except if the player in possession is attempting to ground the ball for a try.

So when it comes to a grey area where the ball is partway out while more than one player is still involved, it comes down to the referee's interpretation – as so many other grey areas do.

Think forward passes that look backwards out of the hand but float forward, or when a player loses control in a play-the-ball while being crowded by a tackler. This is what could be tested by the Bunker this season.

The rule is certainly here to stay for 2020 at least – the competition committee have already decided on rule changes for 2020 and the stripping law will stay as-is for at least this year.